It's been a while my friends since my last post. Perhaps I've been waiting for a subject to arise that might be as potent and personal as was A Year of Stories. So while I am not promising a year, I am inspired to write about prayer: what it means to pray, and how prayer affects us individually and communally. I invite your participation, either in the comment section or as a blog entry in your name. Last Shabbat at morning at Minyan Oneg Shabbat we broke into small groups and in each one read aloud a different poem. After the first reading I asked the groups to distill the poem down to a few words of their own. After the second reading I asked them to choose one line from the poem that spoke to them as the עקר, the essence of the poem. It was thrilling to hear everyone's contribution, and I pointed out that communally they had created their own psalm. Here are the poems. What leaps out at you and resonates with your own relationship with prayer?  Thomas Merton Thomas Merton My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think that I am following your will does not mean that I am actually doing so. But I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you. And I hope I have that desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road, though I may know nothing about it. Therefore will I trust you always, though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for you are ever with me, and you will never leave me to face my perils alone.  Elie Weisel Elie Weisel I no longer ask you for either happiness or paradise; all I ask of You is to listen and let me be aware of Your listening. I no longer ask You to resolve my questions, only to receive them and make them part of You. I no longer ask You for either rest or wisdom, I only ask You not to close me to gratitude, be it of the most trivial kind, or to surprise and friendship. Love? Love is not Yours to give. As for my enemies, I do not ask You to punish them or even to enlighten them; I only ask You not to lend them Your mask and Your powers. If You must relinquish one or the other, give them Your powers. But not Your countenance. They are modest, my requests, and humble. I ask You what I might ask a stranger met by chance at twilight in a barren land. I ask you, God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, to enable me to pronounce these words without betraying the child that transmitted them to me: God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, enable me to forgive You and enable the child I once was to forgive me too. I no longer ask You for the life of that child, nor even for his faith. I only beg You to listen to him and act in such a way that You and I can listen to him together.  Marie Howe Marie Howe Every day I want to speak with you. And every day something more important calls for my attention—the drugstore, the beauty products, the luggage I need to buy for the trip. Even now I can hardly sit here among the falling piles of paper and clothing, the garbage trucks outside already screeching and banging. The mystics say you are as close as my own breath. Why do I flee from you? My days and nights pour through me like complaints and become a story I forgot to tell. Help me. Even as I write these words I am planning to rise from the chair as soon as I finish this sentence.  Mary Oliver Mary Oliver I don’t know where prayers go, or what they do. Do cats pray, while they sleep half-asleep in the sun? Does the opossum pray as it crosses the street? The sunflower? The old black oak growing older every year? I know I can walk through the world, along the shore or under the trees, With my mind filled with things of little importance, in full self-attendance. A condition I can’t really call being alive. Is a prayer a gift, or a petition, or does it matter? The sunflowers blaze, maybe that’s their way. Maybe the cats are sound asleep. Maybe not. While I was thinking this I happened to be standing Just outside my door, with my notebook open, Which is the way I begin every moning. Then a wren in the privet began to sing. He was positively drenched in enthusiasm, I don’t why. And yet, why not. I wouldn’t persuade you from whatever you believe Or whatever you don’t. That’s your business. But I thought, of the wren’s singing, what could this be if it isn’t a prayer? So I just listened, my pen in the air.

0 Comments

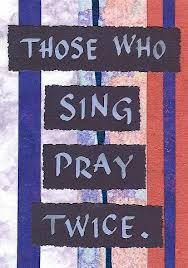

It is now 3 weeks post burial. My chest is a little less heavy, my gait a little freer from the weight of sadness. My beard is sorely in need of trimming, but when I look in the mirror, it doesn't matter, evidenced by the tears that still flow easily as I write this. Luckily, I am frequently in a setting where no one asks about my three weeks of facial hair, I am where everyone knows why my outward appearance is less socially presentable. I am in minyan. As we know, a minyan is necessary for the recitation of certain prayers, among them the mouner's kaddish, an opportunity to sanctify life, and my opportunity to help the return of my mother's soul to its source. Traditionally known as "kaddish yatom", I understand that term more acutely personal now. It is the "orphan's prayer", and I am now without both my mother and father. Reb Zalman would say that I now wear the "white beard". I am the elder. In an interview that she gave after her father died, singer Roseanne Cash shared that, no longer having a living parent, she now felt that "the last barrier between herself and her own mortality had been removed." That powerful insight remained with me, bookmarked for a future date, and was one of the first things that came to mind when my mother Elsie died. This past Sunday morning, as worship began, we only had 9 people. Those of us who were there to say Kaddish were keenly aware of the lack of a quorum to do so. On a weekday someone would have gone across the hall to ask one of the secretaries to join us. But on a Sunday, not so. When we reached the moment to say Kaddish d'Rabbanan, the leader called out a page number that signaled we were skipping Kaddish and moving on to the next section of the liturgy. Immediately, one of the women called out, "Wait, let me see if anyone is coming." The leader paused, and the woman left the room. Those of us remaining sat in silence, and waited - 1 - 2 - 3 - perhaps 5 minutes, before the woman returned with good news in the form of several additional people who were joining us. There was something about the quality of those minutes of silence that deeply resonated within me and between those of us who had sat quietly waiting. Time seemed to stand still. In the stillness I felt held by G!d and community. Reb Zalman teaches a possible understanding for ברוך שם כבוד מלכותו לעולם ועד to be "Your glory shines through time and space." Indeed, in the stillness the glory shined through - so true, so real, so effortless, so comforting. That evening, I returned to shul for Ma'ariv. One woman was saying kaddish for her father. It was her last day, after 11 months, that she needed to do so on a daily basis. She was clearly very emotional, and cried openly. She later shared that it was the anticipation she had about the "last day" that had shaken her. She thanked us all for our presence. I recalled the Kotzker Rebbe's gentle reminder that "there is nothing so whole as a broken heart". I also recognize that there is nothing so whole as a minyan. Ten adult Jews relying on each other's presence - to pray, to remember, to rebuild, to dream awake, and to hold each other in sacred community. This is a well known story, from M. Scott Peck's book, The Different Drum. I include it in this series because (a) I like it and (b) it is used so often within the context of community building. Have you ever had the occasion to use it?  The story concerns a monastery that had fallen upon hard times. Once a great order, as a result of waves of antimonastic persecution in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and the rise of secularism in the nineteenth, all its branch houses were lost and it had become decimated to the extent that there were only five monks left in the decaying mother house: the abbot and four others, all over seventy in age. Clearly it was a dying order. In the deep woods surrounding the monastery there was a little hut that a rabbi from a nearby town occasionally used for a hermitage. Through their many years of prayer and contemplation the old monks had become a bit psychic, so they could always sense when the rabbi was in his hermitage. "The rabbi is in the woods, the rabbi is in the woods again " they would whisper to each other. As he agonized over the imminent death of his order, it occurred to the abbot at one such time to visit the hermitage and ask the rabbi if by some possible chance he could offer any advice that might save the monastery. The rabbi welcomed the abbot at his hut. But when the abbot explained the purpose of his visit, the rabbi could only commiserate with him. "I know how it is," he exclaimed. "The spirit has gone out of the people. It is the same in my town. Almost no one comes to the synagogue anymore." So the old abbot and the old rabbi wept together. Then they read parts of the Torah and quietly spoke of deep things. The time came when the abbot had to leave. They embraced each other. "It has been a wonderful thing that we should meet after all these years, "the abbot said, "but I have still failed in my purpose for coming here. Is there nothing you can tell me, no piece of advice you can give me that would help me save my dying order?" "No, I am sorry," the rabbi responded. "I have no advice to give. The only thing I can tell you is that the Messiah is one of you." When the abbot returned to the monastery his fellow monks gathered around him to ask, "Well what did the rabbi say?" "He couldn't help," the abbot answered. "We just wept and read the Torah together. The only thing he did say, just as I was leaving --it was something cryptic-- was that the Messiah is one of us. I don't know what he meant." In the days and weeks and months that followed, the old monks pondered this and wondered whether there was any possible significance to the rabbi's words. The Messiah is one of us? Could he possibly have meant one of us monks here at the monastery? If that's the case, which one? Do you suppose he meant the abbot? Yes, if he meant anyone, he probably meant Father Abbot. He has been our leader for more than a generation. On the other hand, he might have meant Brother Thomas. Certainly Brother Thomas is a holy man. Everyone knows that Thomas is a man of light. Certainly he could not have meant Brother Elred! Elred gets crotchety at times. But come to think of it, even though he is a thorn in people's sides, when you look back on it, Elred is virtually always right. Often very right. Maybe the rabbi did mean Brother Elred. But surely not Brother Phillip. Phillip is so passive, a real nobody. But then, almost mysteriously, he has a gift for somehow always being there when you need him. He just magically appears by your side. Maybe Phillip is the Messiah. Of course the rabbi didn't mean me. He couldn't possibly have meant me. I'm just an ordinary person. Yet supposing he did? Suppose I am the Messiah? O God, not me. I couldn't be that much for You, could I? As they contemplated in this manner, the old monks began to treat each other with extraordinary respect on the off chance that one among them might be the Messiah. And on the off off chance that each monk himself might be the Messiah, they began to treat themselves with extraordinary respect. Because the forest in which it was situated was beautiful, it so happened that people still occasionally came to visit the monastery to picnic on its tiny lawn, to wander along some of its paths, even now and then to go into the dilapidated chapel to meditate. As they did so, without even being conscious of it, they sensed the aura of extraordinary respect that now began to surround the five old monks and seemed to radiate out from them and permeate the atmosphere of the place. There was something strangely attractive, even compelling, about it. Hardly knowing why, they began to come back to the monastery more frequently to picnic, to play, to pray. They began to bring their friends to show them this special place. And their friends brought their friends. Then it happened that some of the younger men who came to visit the monastery started to talk more and more with the old monks. After a while one asked if he could join them. Then another. And another. So within a few years the monastery had once again become a thriving order and, thanks to the rabbi's gift, a vibrant center of light and spirituality in the realm. (Author unknown) (Note: I prepared this story before my mother died last Thursday at the age of 98. I will be sharing some of her story with you in the weeks to come) ºººººººººººººººººººººººººººººººººººº My late rebbe, R' Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, zt"l, (זכר צדיק לברכה) was a master storyteller. He taught: "a good story is one where the mind surprises the heart". "A Year of Stories" is dedicated to his memory. I invite you to forward the link to these stories so that they find their way into the hearts of other listeners and tellers. ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ Please consider offering a tax deductible donation to support this project and the work of DC's Jewish Renewal community Minyan Oneg Shabbat. A shout out to Judy Young for her generous offering in support of this project. ≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠≠ If you would like to be added to the growing list of "Year of Stories" followers, let me know at [email protected], with "Year of Stories" in the subject line.  Tonight marks the beginning of Tisha B'Av, the 9th day of the month of Av. It is a day of fasting and lament, in which we recall the darkest days of Jewish history, including the destruction of both 1st and 2nd Temples, the expulsion from Spain in 1492, and the sin of the spies, who brought fear to the wandering Israelites instead of hope and promise. It is instructive that following Tisha B'Av we read parshat Va'etchanan, in which we chant our daily mantra - Shma Yisrael Adonai Eloheynu Adonai Echad - the very essence of hope and promise. I say the Shma twice a day, morning and night, always among my last words before drifting off to sleep. Ancient words of surrender, of connection, and of faith. Saying the Shma does not always however have that affect on people, as I recently learned after leading a Ma'ariv service at the Jewish Renewal Kallah. For a long time I had wanted to lead a congregation in its recitation of the Shma as I did at Kallah. I asked everyone to begin saying the words very, very quietly, attending to the words being spoken by his/her neighbor. They were to slowly get louder and louder, listening to each other, until together everyone's voices reached a crescendo, at which point their voices would subside, like an ocean's ebb and flow, until the last person's voice trailed off. It worked beautifully, just the way I had heard it in my mind. It devestated at least two members of the kahal. The next day two women approached me at separate times to tell me about their experience. Both had had the same experience, a powerful one which they never wanted to repeat again. While chanting the Shma rthe night before, they found themselves in a death camp, slowly walking with others to the gas chamber, chanting, no shouting the words of the Shma together with everyone else. The shouts got louder and louder, until their voices were heard no more. I lstened, and understood that I could never again lead the recitation of the Shma in that way. Tonight and tomorrow, I will recall the unalterable destruction perpetrated throughout history on my people. It will serve for me as the starting point for the next seven weeks in preparation for Rosh HaShana and Yom Kippur. And I will begin by remembering that the six words of the Shma have had power for others throughout history that is far beyond anything that I might ever contemplate.  Hanging to my left on the wall in my office is this card: "Those Who Sing Pray Twice." Like most of what I am surrounded by (G!d forbid this should ever include the loved ones in my life), I take little day to day notice of. But I couldn't help gain some new insight into what this quote may mean in the light of this week's Torah portion, Parshat Chukat. The most famous instance that we find B'nai Yisrael breaking into spontaneous song is after its perilous flight from Egypt and its subsequent crossing of the sea. The Song of the Sea begins: אָז יָשִׁיר-מֹשֶׁה וּבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל אֶת-הַשִּׁירָה הַזֹּאת (Exodus 15:1) Then sang Moshe, and all the Israelites with him, this song... So too in Pasrhat Chukat do we find Israel breaking into song after another act of Divine salvation, this time from the hands of the Amalekites (disguised, according to Rashi, as Cannanites):אָז יָשִׁיר יִשְׂרָאֵל, אֶת-הַשִּׁירָה הַזֹּאת (Numbers 21:17) Then did Israel sing this song....(doo-daa, doo-da) What is the connection? A line from Psalms gave me a clue: לַיהוָה הַיְשׁוּעָה עַל-עַמְּךָ בִרְכָתֶךָ סֶּלָה. (Psalms 3:9) Rescue is the Lord's! On Your people your blessing (Alter translation) The midrash on this psalm helped me understand somethng new. Midrash Tehillim unpacks this line to mean “for all the miracles you do for us it is our obligation to sing songs for you” According to the midrash then, a blessing = a song. As the card says: "Those Who Sing Pray Twice." In a more modern context, from where does spontaneous song arise? In a beautiful interview, Roseanne Cash, the daughter of the legendary musician and songwriter Johnny Cash, comments on her music writing process: "I think that when you're in that creative zone, you're tapping into the collective unconscious, and that there's a field there. I think that's the unified field, that creative vast unconsciousness full of beauty and love. And when you're in the zone, as a writer, as a painter, as a cook--any creative endeavor--you can draw on it. Sometimes I feel like the songs are already out there... It's not that way with all of them...(but) some of them are infused with the radiance of truth, and those are the ones that I think come from that unified field, from God, from what I think of as God. That doesn't mean I'm extra special, by the way. That means everyone has access to it." Collective unconscious, unified field, שמע ישראל. B'nai Yisrael breaks into song after rescue because it is for them, as it is for me, a moment in which my senses are in a heightened state of awareness. I'm more tuned in, and channel provides better reception. I'm in the zone. May we all be blessed to sing our song, whether it rise up in times of plenty or in times of trouble. And may our songs be drawn from the Infinite well, a song that in turn draws us back to our source. "Those Who Sing Pray Twice." |

Mark Novak is a "free-range" rabbi who lives in Washington DC and works, well, just about everywhere. In 2012 he founded Minyan Oneg Shabbat, home to MOSH (Minyan Oneg Shabbat), MindfulMOSH (Jewish mindfulness gathering), and Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed