My mother, Elsie Novak, died on November 6. May her memory be for a blessing My mother, Elsie Novak, died on November 6. May her memory be for a blessing I recall times when as I child I lay sick in bed. My mother would gently rub Vick's VapoRub on my chest, and then cover it with a dry wash cloth. So warm, so soothing, so mentholated. Even now I can feel my mother's hand doing its magic. And when I look at my hands, I see hers - freckled, thin, and yes, aging. If only my hands could pass on comfort as my mother's did. This story took place in the north of Lebanon in the village of Hamadin. And the happening, as told, goes like this: In the village lived a widow and her beautiful daughter, an only child. One day the daughter became ill and was ordered to rest. And so she lay on her bed near the window and looked out at the only tree in the yard. Thus, days, weeks, and months passed, and the autumn came. But the girl's condition didn't improve. On the contrary, she grew worse. And so, one day, as she looked at the tree, she said weakly, "You see, Mother, see those leaves. When the last leaf falls, I will die." The mother's heart grieved, and she watched anxiously as the leaves fell. One cold night the wind howled, and the mother's heart was full of despair, as she saw the wind taking the last leaves. With every leaf her heart sank even deeper. At last there was only one leaf left. What could she do? So the poor woman ran outside, unaware of the cold, the gusts of wind, and the storm. She approached the wall in front of the tree, and there she painted, on the wall, a picture of the last leaf. So good, so accurate was the drawing, that it looked like the last leaf itself. When the girl awoke, she looked out the window, and there she saw one lonely leaf. Days and weeks passed. From time to time she looked out, amd always she saw that last leaf, still hanging on the branch of the tree, A new spirit entered the girl. Slowly, slowly she recovered, and at last she got well. But the mother, by going out on that windy night, had caught cold. She developed tuberculosis, and soon died. When the girl was able to leave her bed, she went outside to see the miracle that had occured: Why had that leaf not fallen? And what did she see? The painting, done by her mother, which had cost her her life for her child's sake. Then the girl realized her mother's great love, and grieved greatly for her mother who, in her own death, had given life to her. The Mother, a Lebanese Folktale, retold by Barbara Rush, from The Jewish Spirit: A Celebration in Stories & Art ººººººººººººººººººººººººººººº

My late rebbe, R' Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, zt"l, (זכר צדיק לברכה) was a master storyteller. He taught, in the name of Abraham Joshua Heschel zt"l: "a mayse is a story in which the soul surprises the mind". "A Year of Stories" is dedicated to his memory. I invite you to forward the link to these stories so that they find their way into the hearts of other listeners and tellers. ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ Please consider offering a tax deductible donation to support this project and the work of DC's Jewish Renewal community Minyan Oneg Shabbat. If you would like to be added to the growing list of "Year of Stories" followers, let me know at [email protected], with "Year of Stories" in the subject line.

0 Comments

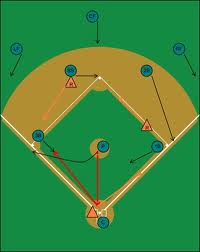

A major story this past week was the court victory for Women of the Wall. While we can't predict what will happen in the next few months, the victory illustrates both the evolving nature of the Jewish world, and what can be accomplished in the continuing struggle for inclusivity when passion is wed to the willingness to take risk. It took 20 years for this this day to come. You may have noticed that this post's title is "Woman of the Wall", and not "Women of the Wall." That is because as a result of the action of many brave and relentless women, the boundary of where and how women can pray at The Western Wall has been moved. It reminded me of the following true story, about a woman, and a wall. Lee Bluemel, a Unitarian Universalist minister tells the story: "It happened in the years preceding the Second World War. A Quaker woman came to work as a nurse in a small Catholic village in Poland. There were no other nurses or doctors there, so the Quaker nurse did just about everything. She birthed the babies, tended the sick, set broken bones, cared for the dying. There was plenty to do, and it was good work, so the Quaker nurse stayed on. She stayed for the year, and then a second year, and a fourth year, a tenth year and by then the villagers stopped counting. The Quaker nurse was practically one of them. The villagers loved her. The first babies she had delivered turned into fine young men and strong young women. Their aging mothers came to her with confidences and hot chicken pot pies. Then one day the Quaker nurse died. The villagers needed a place to say their good-byes and bury the body so she could rest in peace. But the village was a small one, and it had only one cemetery – A Catholic cemetery. You couldn’t bury a Quaker nurse in a Catholic cemetery. It was illegal. There was nowhere for her to go ...or so it seemed. The villagers got together. They asked one another: What could be done? After much deliberation, they decided to bury the Quaker nurse just outside the cemetery’s stone wall. It was the best they could do. The young men dug the grave, the villagers said their good-byes. They had loved her. Some cried. Then as the sun began to set, slowly they walked back to their homes. Darkness came. All was quiet.......Except for one sound – an odd sound—out be the cemetery. If you listened very carefully, you could tell it was the sound of stone scraping against stone. And, there was another sound too – the sound of labored breathing. The young men and the young women were moving the stones of the cemetery wall. They worked in silence, breathing hard, with the help of their mothers and fathers. When the sun came up the next day, it turned out that the Catholic cemetery in the little Polish village was just a bit larger than it ever had been before. As for how it got that way, when the villagers were asked, no one seemed to know. But the next night all of the villagers – even the Quaker nurse – rested in peace.”  Yesterday morning was the once a month gathering of my nascent community, Minyan Oneg Shabbat. At first I had a twinge of dissappointment, as we had "only" 12 people who attended, the smallest turnout since our November start. But as our morning of devotional prayer progressed, it proved the adage "sometimes less is more" in a most powerful way that I could ever have imagined. Being so few in number allowed us all the opportunity to gather around the sefer Torah as it was chanted. Since Parshat Vayikra begins the description of the sacrifices commanded of the wandering nation, after the reading my chevra and I took the opportunity to unpack the meaning of sacrifice as we understand it. Laurie, an oncology nurse, shared the following - she told us that when a doctor needs to remove cancerous growth from the body of a patient, that s/he refers to it as a sacrifice, and communicates as such to the patient. In other words, the patient sacrifices/gives up something - i.e. a breast, or part of a stomach - for the sake of a larger purpose. In this case for the sake of life itself. In silence we stood together, with the Torah as witness, digesting the full impact of this. Never could we have imagined that the expression "less is more" and the reading of the sacrificial rites would have intersected in such a profound and humbling manner.  Yesterday I asked Ben, my bar mitzvah student and fellow baseball lover, how he would define the word "sacrifice". He replied that "it is when you give something up fo yourself in order to benefit others or yourself." I was struck by his insight, and was delighted to happen upon the image to the left of what happens on a baseball field when a batter sacrifices himself for the benefit of the team. Notice that his intention/action sets every other player on the field in motion. Not one player on the field is unmoved by the action of a single member of its community. The ripple affect caused by an act of giving. |

Mark Novak is a "free-range" rabbi who lives in Washington DC and works, well, just about everywhere. In 2012 he founded Minyan Oneg Shabbat, home to MOSH (Minyan Oneg Shabbat), MindfulMOSH (Jewish mindfulness gathering), and Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed