A major story this past week was the court victory for Women of the Wall. While we can't predict what will happen in the next few months, the victory illustrates both the evolving nature of the Jewish world, and what can be accomplished in the continuing struggle for inclusivity when passion is wed to the willingness to take risk. It took 20 years for this this day to come. You may have noticed that this post's title is "Woman of the Wall", and not "Women of the Wall." That is because as a result of the action of many brave and relentless women, the boundary of where and how women can pray at The Western Wall has been moved. It reminded me of the following true story, about a woman, and a wall. Lee Bluemel, a Unitarian Universalist minister tells the story: "It happened in the years preceding the Second World War. A Quaker woman came to work as a nurse in a small Catholic village in Poland. There were no other nurses or doctors there, so the Quaker nurse did just about everything. She birthed the babies, tended the sick, set broken bones, cared for the dying. There was plenty to do, and it was good work, so the Quaker nurse stayed on. She stayed for the year, and then a second year, and a fourth year, a tenth year and by then the villagers stopped counting. The Quaker nurse was practically one of them. The villagers loved her. The first babies she had delivered turned into fine young men and strong young women. Their aging mothers came to her with confidences and hot chicken pot pies. Then one day the Quaker nurse died. The villagers needed a place to say their good-byes and bury the body so she could rest in peace. But the village was a small one, and it had only one cemetery – A Catholic cemetery. You couldn’t bury a Quaker nurse in a Catholic cemetery. It was illegal. There was nowhere for her to go ...or so it seemed. The villagers got together. They asked one another: What could be done? After much deliberation, they decided to bury the Quaker nurse just outside the cemetery’s stone wall. It was the best they could do. The young men dug the grave, the villagers said their good-byes. They had loved her. Some cried. Then as the sun began to set, slowly they walked back to their homes. Darkness came. All was quiet.......Except for one sound – an odd sound—out be the cemetery. If you listened very carefully, you could tell it was the sound of stone scraping against stone. And, there was another sound too – the sound of labored breathing. The young men and the young women were moving the stones of the cemetery wall. They worked in silence, breathing hard, with the help of their mothers and fathers. When the sun came up the next day, it turned out that the Catholic cemetery in the little Polish village was just a bit larger than it ever had been before. As for how it got that way, when the villagers were asked, no one seemed to know. But the next night all of the villagers – even the Quaker nurse – rested in peace.”

0 Comments

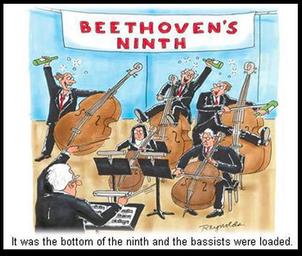

One of my visions for Minyan Oneg Shabbat, the nascent Jewish Renewal community that I started last November here in Washington, DC, is for our Shabbat service to provide an opportunity for members of the kahal to share their Torah, their story, and to see their story as imbedded in our story - the Torah. A week prior to each Shabbat that we meet I set a kavvanah, an intention for the service based on the parsha , and then invite members of the kahal to bring in a poem, a song, a chant, or a story as an offering. I then weave their offerings into the body of the service, and together with music and song, silence and discussion, t'fillah and Torah, we make magic. There is something very important about being seen and being heard. This past Shabbat we read a double parsha, Acharei Mot/Kedoshim. Amitai Gross, who I will miss dearly when his journey continues in graduate school at Brandeis this fall, offered this piece of his heart. With his permission, I am proud to share it with you. Great Holiness by Amitai Gross I believe in an ever-present-yet-ever-distant, all-encompassing, life-force, beyond our comprehension and completely personal at the same time, existing and non-existing at the same time, inhabiting, encompassing, and completely outside of the constantly-expanding Universe, which is, was, and will be forever creating, shifting, molding, and recreating, setting in motion, and supporting all life, matter, and energy, real and imaginative, breathing and not, always over-simplified, humanized, characterized, attributed, and limited with names, titles, and descriptions, culminating in a nasty three-letter word: God. This nothing that is everything that is thing and not-thing encompasses the entirety of the Universe, within, and without. All of creation that was not created but always was a part of something vast and infinitesimal, six-day, big bang, and circular timeline, is part of the Great Holiness that is all and everything and nothing. This Great Holiness, this Sacred Beyond Reality, embraces all that we know and all that we don’t. In all of everything, we must be naïve to believe that of every galaxy of stars, ours is the Holiest. In all of everything, me must be fools to believe that of every sun in the galaxy, our is the Holiest. In all of everything, we must be children to believe that of every planet, full of life, be it bacterial, plant, or animal, our planet and our humans are the Holiest. Our humanity is only one part of the great cosmic unknown that we exist within. Our tribes are simply specs within the great expanse of life. Our holy cities, be they Jerusalem, Mecca, Medina, Rome, Bethlehem, The Saptapuri, or Salt Lake City, are only Holy because we’ve dubbed them so. Our holy books called Bible, Torah, Quran, Gita, Tao, Mormon, Kitab-I-Aqdas, or otherwise were created by our own hands. Our leaders and teachers, Jesus, Muhammad, Smith, Moses, Buddha, and countless Babas, are simply humans. They are no more part of the Great Holiness than you or I. They are no less part of the Great Holiness than you or I.  I go to shul to pray in community nearly every Shabbat. I go to Nats Stadium to watch and root in community a number of times a year. And I read the sports section of the Washington Post nearly every day. After the Boston bombing I started thinking about the idea of community and what it means to be a part of one. And then sportswriter Tracee Hamilton wrote about that very subject. I read her paper - she must have been reading my mind. The article pointed out just how vulnerable spectators are at sporting events, and that perhaps one day soon, partly because of security concerns. people may choose to stay home. That would be a great loss she notes, because being a member of a sports community is all that some people have. Where would that choice leave many? Plugged into personal communication devices that estrange us from a sense of community. (Maybe some day someone will invent the wePad) Interestingly, a reader wrote to the Post objecting to Hamilton’s premise about loss of community. “Isn’t the online community a community?” he asked. I am not going to comment on that, but rather look to last week’s Torah portion for guidance, where at the beginning of Parshat Kadoshim G!d says “You shall be holy”. The word “you” is stated in the plural, and the declaration is meant to be addressed by Moshe to "adat Yisrael", the entirety of the congregation of Israel. The Chatam Sofer comments that this holiness refers to holiness that can only be attained in community, holiness that springs forth from relationship with one’s neighbor. (“v’ahavta, rey’echa kamocha” - love your neighbor as yourself - appears a few lines later) The Chatam Sofer is teaching that we should seek G!d in community, that isolating oneself in the search for holiness is not the ideal. I suspect that the Rebbe never once went to a ballgame.  I am humbled every time I am reading a Jewish text and the following words appear: "As we know...", which is then followed by the teaching itself. Why? Because apparently the teaching is a common one that EVERYONE knows. "Everyone", of course, except for me. Today the teaching was on the word ADaM, which, "as we know", is an acronym for "ADaM David Mashiach". What ADam? Who is the person who will lead us towards the long promised messianic age of peace? Why, according to the teaching, it's me, and you, and every other human being that has ever been and will ever be born. This is called "messianic consciousness. There is a story of Rebbe Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk as told in Pillar of Prayer, "Once, while he was studying in his synagogue, someone burst in and shouted that the Messiah had just revealed himself in the Galilee. The Rebbe left the house and courtyard, and took a whiff of the air in the public thoroughfare and announced "nothing has changed." Hasidim explained that the reason the Rebbe had to leave the synagogue for the public street is because as far as he was concerned, Messianic consciousness is already present." And so it is, in the aftermath of Boston, that I am reminded not only of heroes, but of the promise of Messiah, and the concept that each of us has a messianic spark. I am also reminded of a story that "everyone knows", "The Rabbi's Gift", which appears in M. Scott Peck's The Different Drum: Community Making and Peace. I share an abbreviated version with you here. The story concerns a monastery that had fallen upon hard times. It was once a great order, but because of persecution, all its branch houses were lost and there were only five monks left in the decaying house: the abbot and four others, all over seventy in age. Clearly it was a dying order. In the deep woods surrounding the monastery there was a little hut that a rabbi occasionally used for a hermitage. The old monks had become a bit psychic, so they could always sense when the rabbi was in his hermitage. "The rabbi is in the woods, the rabbi is in the woods" they would whisper. It occurred to the abbot that a visit the rabbi might result in some advice to save his monastery. The rabbi welcomed the abbot to his hut. But when the abbot explained his visit, the rabbi could say, "I know how it is" . "The spirit has gone out of the people. It is the same in my town. Almost no one comes to the synagogue anymore." So the old abbot and the old rabbi wept together. Then they read parts of the Torah and spoke of deep things. When the abbot had to leave, they embraced each other. "It has been a wonderful that we should meet after all these years," the abbot said, "but I have failed in my purpose for coming here. Is there nothing you can tell me that would help me save my dying order?" "No, I am sorry," the rabbi responded. "I have no advice to give. But, I can tell you that the Messiah is one of you." When the abbot returned to the monastery his fellow monks gathered around him to ask, "Well what did the rabbi say?" “The rabbi said something very mysterious, it was something cryptic. He said that the Messiah is one of us. I don't know what he meant?" In the time that followed, the old monks wondered whether the significance to the rabbi's words. The Messiah is one of us? Could he possibly have meant one of us monks? If so, which one? Do you suppose he meant the abbot? Yes, if he meant anyone, he probably meant Father Abbot. He has been our leader for more than a generation. On the other hand, he might have meant Brother Thomas. Certainly Brother Thomas is a holy man. Everyone knows that Thomas is a man of light. Certainly he could not have meant Brother Elred! Elred gets crotchety at times. But come to think of it, even though he is a thorn in people's sides, when you look back on it, Elred is virtually always right. Often very right. Maybe the rabbi did mean Brother Elred. But surely not Brother Phillip. Phillip is so passive, a real nobody. But then, almost mysteriously, he has a gift for always being there when you need him. He just magically appears. Maybe Phillip is the Messiah. Of course the rabbi didn't mean me. He couldn't possibly have meant me. I'm just an ordinary person. Yet supposing he did? Suppose I am the Messiah? O God, not me. I couldn't be that much for You, could I? As they contemplated, the old monks began to treat each other with extraordinary respect on the chance that one among them might be the Messiah. And they began to treat themselves with extraordinary respect. People still occasionally came to visit the monastery in its beautiful forest to picnic on its tiny lawn, to wander along some of its paths, even to meditate in the dilapidated chapel. As they did so, they sensed the aura of extraordinary respect that began to surround the five old monks and seemed to radiate out from them and permeate the atmosphere of the place. There was something strangely compelling, about it. Hardly knowing why, they began to come back to the monastery to picnic, to play, to pray. They brought their friends to this special place. And their friends brought their friends. Then some of the younger men who came to visit the monastery started to talk more and more with the old monks. After a while one asked if he could join them. Then another, and another. So within a few years the monastery had once again become a thriving order and, thanks to the rabbi's gift, a vibrant center of light and spirituality in the realm.  "When I was a boy and and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, "Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping." To this day, especially in times of disaster, I remember my mother's words, and I am comforted in realzing that there are still so many helpers, so many caring people in this world." "We live in a world in which we need to share responsibility. It's easy to say "It's not my child, not my community, not my world, not my problem." Then there are those that see a need and respond. I consider those people my heroes." "It's very dramatic when two people come together to work something out. It's easy to take a gun and annihilate your opposition. but what is really exciting to me is to see people with differing views come together and finally respect each other." Keyn Y'hi Ratzon.  ....walk into a bar. The bartender looks up and says, "What is this, a joke or something?" Anyone who knows me knows that I have been blessed with the gift of a sense of humor. I am not talking about joke telling, because I can hardly remember any of the jokes I've been told. I am talking about the ability to elicit laughter from a situation. Yes, sometimes I get an eye roll from my 17 year old daughter Kaziah, but that's her job, and I usually deserve it. But more often she laughs, which was one of the things my wife Renée blessed her with at her baby naming, "May you always laugh at your father's jokes." There is something deeply instrinsic to the human spirit about being joyous, as we learn from many Hasidic teachings. The Tanach and the Talmud are replete with humor, as I was reminded during a study session with my chevruta yesterday morning. In BT Taanit 22a is a story of Rabbi Baruqa, who one day happened upon the prophet Elijah in the marketplace. He asks the prophet, "Is there anyone among the people here in the marketplace who have a place in the World to Come?" Elijah answered that 'there is none." Later two men entered the marketplace and Elijah pointed them out, saying, "Those two will have a share in the World To Come". "Rabbi Bauqa asked the two men their occupations. "We are jesters" they replied, "when we see someone who is sad we cheer him up. When we see two people quarreling we try to make peace between them." The Baal Shem Tov teaches that the job of these two merry-makers is to remind us of our true nature, to reactivate the passive aspect of the Divine that are lying latent in our deeds and words. The "passive aspect of the Divine"? Why joy of course! What an occupation! What a calling! Imagine a want ad: Jester needed, to use your sense of humor to unite with others; could be a person who is in a state of pain and despondency. Ability to unite a person to His blessedness required. In his book "Pillar of Prayer", a recent translation of the teachings of the Baal Shem Tov on prayer, Menachem Kallus writes "using humor for a higher purpose and imbuing all of one's words with intentional significance" is, according to the Besht, an important priniciple. What is this, a joke or something? It sure is - an important tool of Rebbe-craft.  I recently found out that for the last 10 years, NYU president John Sexton has been teaching a course "Baseball as a Road to G!d". It's always nice to have a university president confirm something that I have sensed for the last 50 years! I have every intention of buying his book by the same name, perhaps two, one for me and one for my baseball crazy bar mitzvah student Ben. A few days ago I was pleasantly surprised upon opening a different book, "The Spirituality of Imperfection", to find this baseball quote: "Baseball teaches us...how to deal with failure. We learn at an early age that failure is the norm in baseball and, precisely because we failed, we hold in high regard those who fail less often - those who hit safely in one out of three chances and become star players. I also find it fascinating that baseball, alone in sport, considers errors to be part of the game, part of its rigorous truth." This was written by former baseball commissioner Faye Vincent, Jr. Let's call it the Torah of Baseball. Hmmm.... maybe I'll write a proposal to teach it at American University!  My friend Dina played the word kvass the other day in Scrabble. I sent her an IM, "where the heck do you get these words?" to which she replied, "Someone played it against me and I remembered it." Unbelievable - I can't remember the details of what I studied this morning and she remembers k-v-a-s-s for 43 points. Later that day I was immersed in reading Aleksander Hemon extraordinary novel "The Lazurus Project", and was floored when I read about the Cossack who "stank of garlic and kvass." Kvass! What were the odds? So now I had to look it up. Turns out it is fermented beverage made from rye or black bread, with a relatively low alchohol content. I guess it gave the Cossacks enough of a jolt to propel them while they raped, pillaged, and killed Jews in the Kishinev progrom of 1903. JJ Goldberg writes in The Forward: "Provoked by a medieval blood libel, flashed around the globe by modern communications, Kishinev was the last pogrom of the Middle Ages and the first atrocity of the 20th century. The event, and the worldwide wave of Jewish outrage that it evoked, laid the foundations of modern Israel, gave birth to contemporary American-Jewish activism and helped bring about the downfall of the czarist regime." I'd call that a pivotal event, and one that I was not very familiar with. I spent the next few hours reading about the massacre, which led me to a poem written about it by the young Hebrew poet Chayyim Nachman Bialek: Descend then, to the cellars of the town, There where the virginal daughters of thy folk were fouled, Where seven heathen flung a woman down, The daughter in the presence of her mother, The mother in the presence of her daughter, Before slaughter, during slaughter, and after slaughter! Touch with thy hand the cushion stained; touch The pillow incarnadined: This is the place the wild ones of the wood, the beasts of the field With bloody axes in their paws compelled thy daughters yield: Beasted and swined! Note also, do not fail to note, In that dark corner, and behind that cask Crouched husbands, bridegrooms, brothers, peering from the cracks, Watching the sacred bodies struggling underneath The bestial breath, Stifled in filth, and swallowing their blood! Watching from the darkness and its mesh The lecherous rabble portioning for booty Their kindred and their flesh! Crushed in their shame, they saw it all; They did not stir nor move; They did not pluck their eyes out; they Beat not their brains against the wall! Perhaps, perhaps each watcher had it in his heart to pray: A miracle, O Lord, and spare my skin this day! Between the scene in the book, and this poem, two heart wrenching desriptions of Jewish victimization. The only problem is that Bialek got it all wrong about Jewish passivity (read more about that here) Whew, from k-v-a-s-s to Kishinev to Bialek. I'll remember that. I do admit that I play a lot of, perhaps too much at times, online Scrabble, when I could be doing far more useful things with my time. Like drinking kvass. |

Mark Novak is a "free-range" rabbi who lives in Washington DC and works, well, just about everywhere. In 2012 he founded Minyan Oneg Shabbat, home to MOSH (Minyan Oneg Shabbat), MindfulMOSH (Jewish mindfulness gathering), and Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed