I have memory of my father, Abraham Novak (z"l) , chanting. making his way through the haggadah at stunning speed, interrupted occasionally by my mother peeking out of the kitchen, asking "how much longer until dinner?" I have memory of my father singing, always a Jewish liturgical song, in his rich deep bass, a voice that held up the world. I have memory of my father working, standing over the cutting table at his dress factory, cigar in hand, ruling his small "empire" that employed 20 people for 40 years. I have memory of my father smoking his cigar, his constant companion every day, except on Shabbas. My mother would ask, "Adolph, why can't every day be Shabbas?" I have memory of me and my father playing catch on the side of our house. He is wearing a white tee shirt, shorts, black socks and shoes, tossing a hard ball with me, back and forth, as time stands still. Is this heaven? (Yes, I do weep, every time, at the end of Field of Dreams) I have memory of my father eating, always with a yarmulke on his head. He expected me and my brother to always wear one at the table as well. I remember one day as a teenager sitting down at the table, beggining to eat purposely without my head covered. I hear my father say to my mother, "Tell your son that at my table we wear a yarmulke." I have no memory of my father crying. I have memory of my father selling cans upon cans of maccaroons to everyone he possibly could - in his workplace, on the subway, in the neighborhood. With his help I win the #1 prize in the religious school contest for selling maccaroons - a radio that clips on to my bicycle handle. I have memory of my father lying in bed at the hospital. Although he cannot open his eyes nor utter a word, he hears me singing to him, L'dor Va'dor, and instinctively, through labored breathing, he reaches for the harmony part. For all that you gifted me with dad, I thank you. When I say Kaddish for you, through the gift of memory you are reborn, allowing me, once again, to feel your presence. I never died said he.

1 Comment

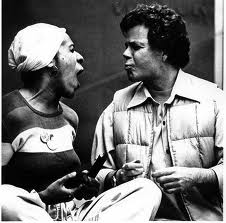

THis past Sunday, March 17, was the birthday of the late Bob Alexander, founder and director of the Living Stage Theater Company, which I served from 1977-1985. (Bob is seen here with the late Rebecca Rice, actress/director, and theater worker extraordinare) Despite his distrust for all things "religious", and disassociation from his Jewish heritage, Bob was my rebbe. One of his favorite quotes was: "In the deepest part of our soul, in the deepest parts of our humanity, we have the need to create. to transform the visciousness and mediocrity of the world into sunlight and peace. Welcome to the place where you can dare to be in your dreams, dare to be strong, dare to be vulnerable. All power to the imagination Love and good courage" It is astonishingly clear to me that these words speak of our soul's longing, pushing and struggling to recognize itself, often in opposition against the realities of the world into which it was born. We were born into this world to create. We are, in Jewish thought, co-creators with the Divine. Creativity, the most powerful way to act in a Godly manner, is our birthright. And it is, like Pablo Casals wrote, "not something to turn on and off like tapwater", but rather the way to live life. In the moment of creation we are "like G!d", all pretense and ego is stripped away, and we are channels for something far greater than ourselves. Truth is revealed, and if we are so blessed, light shines on and through us. Like Moses descending Sinai, we are radiant, and truly free. In its most radical understanding, this means that humankind need not wait for a single messiah to herald the coming of a world perfected. That messenger is here, right now, and is born every minute of every day. If only we could listen, and truly hear his/her message. From "It's In Everyone of Us", by David Pomerance, one of Bob's favorite songs: "It's in everyone of us To be wise Find your heart Open up both your eyes We can all know everything without ever knowing why It's in everyone of us, by and by."  Yesterday morning was the once a month gathering of my nascent community, Minyan Oneg Shabbat. At first I had a twinge of dissappointment, as we had "only" 12 people who attended, the smallest turnout since our November start. But as our morning of devotional prayer progressed, it proved the adage "sometimes less is more" in a most powerful way that I could ever have imagined. Being so few in number allowed us all the opportunity to gather around the sefer Torah as it was chanted. Since Parshat Vayikra begins the description of the sacrifices commanded of the wandering nation, after the reading my chevra and I took the opportunity to unpack the meaning of sacrifice as we understand it. Laurie, an oncology nurse, shared the following - she told us that when a doctor needs to remove cancerous growth from the body of a patient, that s/he refers to it as a sacrifice, and communicates as such to the patient. In other words, the patient sacrifices/gives up something - i.e. a breast, or part of a stomach - for the sake of a larger purpose. In this case for the sake of life itself. In silence we stood together, with the Torah as witness, digesting the full impact of this. Never could we have imagined that the expression "less is more" and the reading of the sacrificial rites would have intersected in such a profound and humbling manner.  On Tuesday I visited my friend Stuart at a federal penitentiary, where he has been incarcerated for nearly two years, still awaiting sentencing. As I waited in the lobby, I noticed a women between 60-70 sitting and reading tehillim (psalms). I knew immediately who she was. She was the wife of the man who was responsible for Stuart's situation. My mind imediately began planning on somethng to say to her: "You shoukd be ashamed of yourself", or worse "May God multiply your pain and suffering." In the end, I restarined myself andI did not say anything to her. When I arrived upstairs to the visitng room to meet with Stuart, I noticed that she sat down with a young inmate about 30 years of age. Of course! It was her son, also indicted in the same scheme, along with his father and my friend Stuart. I looked over, and caught the son's eyes. I wanted to strangle them both. Gevalt, what was I thinking? Stuart and I settled into a wonderful hour of conversation, much of it centering on his faith in HaShem, his faith that he was in prison for a reason, and that the time there had allowed him to sort through and make some sense of his life. Suffering from poor eyesight, he shared with me that HaShem had literally and figuritively opened his eyes, and that now he more clearly understood the arc of his story and why he was where he was supposoed to be at this moment in time. "And the man and woman over there?" I asked him. He confirmed who they were, but he harbored no resentment nor anger towards either of them. I compared my reaction to these people with my friend's state of mind towards them. My impulse was one of amger and resentment, and his place was one of equanimity and forgiveness. Clearly I was imprisoned as well. Two different quotes came to mind. The first was from George Jackson, who wrote in his autobiography Soledad Brother: "Locked in jail within a jail, my mind is still free. I refuse ever to allow myself to be forced by living conditions into a response that is not commensurate with my intelligence and my final objective." The second was from Maya Angelou's I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings: " “A free bird leaps on the back of the wind and floats downstream till the current ends and dips his wing in the orange suns rays and dares to claim the sky. But a bird that stalks down his narrow cage can seldom see through his bars of rage his wings are clipped and his feet are tied so he opens his throat to sing. The caged bird sings with a fearful trill of things unknown but longed for still and his tune is heard on the distant hill for the caged bird sings of freedom. The free bird thinks of another breeze and the trade winds soft through the sighing trees and the fat worms waiting on a dawn-bright lawn and he names the sky his own. But a caged bird stands on the grave of dreams his shadow shouts on a nightmare scream his wings are clipped and his feet are tied so he opens his throat to sing. The caged bird sings with a fearful trill of things unknown but longed for still and his tune is heard on the distant hill for the caged bird sings of freedom.” In this season of liberation, may we all "see through (our) bars of rage", and sing a song of freedom.  Reb Zalman speaks of prayer as a spritiual tool that is useful in helping us to recalibrate. I take that to mean that the insight gained from prayer guides me to re-member who and what G!d intended for me upon conception (Hmmm....G!d's or mine?) A few weeks ago I planted a number of broccoli seeds, which are now 1 1/2 inches tall and reaching towards the light, awaitng their transplanting upon spring's arrival. How does the broccoli seeed know what it is and what it will become? What do I have to learn from its wisdom? Perhaps part of the answer lies in Hanna Tiferet's beautiful song "Planting Seeds". On this Shabbas, may we all be reminded of who we are.  My morning davvenen this morning consisted of the following: 1) Putting on my tallis (my late father's tallis is my weekday davvenen tent of meeting) 2) Laying tefillin 3) Lighting a candle and taking a few moments in hitbodedut 4) Sitting next to the window that overlooks my garden 5) Listening to Reb Zalman teach about Psalm 23 (it's always good to hear Reb Zalman's laugh to start the day) 5) Listening to Bobby McFerrin's setting for Psalm 23 With eyes closed, I sit in silence - bathing in the sunlight streaming through my window, bathed in the miracle that is McFerrin's inspired gift. With tears streaming down my face, I am ready to face the day. |

Mark Novak is a "free-range" rabbi who lives in Washington DC and works, well, just about everywhere. In 2012 he founded Minyan Oneg Shabbat, home to MOSH (Minyan Oneg Shabbat), MindfulMOSH (Jewish mindfulness gathering), and Archives

June 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed